To an outsider, the decisions single parents make to ensure the financial survival of their families may seem desperate, thoughtless, irresponsible or maybe reckless.

From one job to the next, from one shift to the next, from one place to the next, we know the stability of our families depends on our determination to seek and be better. Thus, when opportunities present themselves, we must identify them and act.

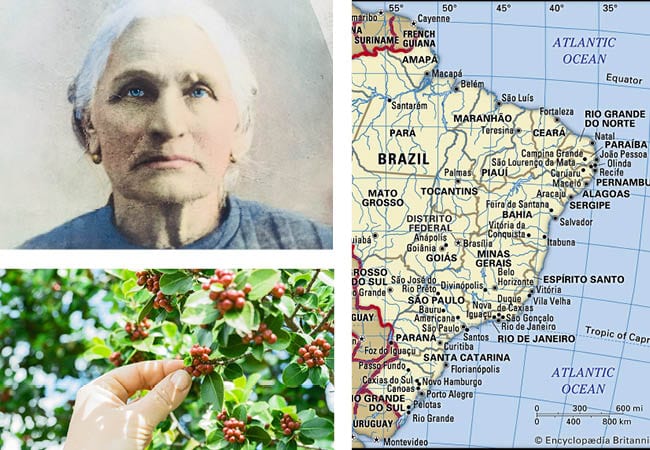

Facing the hungry mouths and anxious hearts of eight children, my great-great-grandmother believed that their financial happiness and security could be achieved on the coffee plantations of Brazil. At least that was the carefully crafted messaging of Brazil’s campaign to replace former slaves with migrant laborers.

With her husband dead and her father unable or unwilling to help her, what could she do in the 1890s? This story of her courage and determination has been passed down through the generations of my family, and I now share the remainder of it with you.

Planning her escape

My great-great-grandmother was left with a drastic decision when she realized that the safety and well being of her children and herself were at risk.

Somehow she paid a transient worker a sum of money to bring her a wooden cart. In that cart, she loaded her children and what belongings they possessed and fled the coffee plantation in the dead of night.

The contract she signed be damned!

My mother who shared this account with me believes my great-great-grandmother traveled to a port city, possibly the one her ship docked in when she and her children arrived.

This part of her life is filled only with questions, the hoped-for answers having faded and disappeared with the passing of each memory keeper.

Did the plantation owner pursue her and her children for running away? How did she and her children survive? Did they find work?

And how long were they in Brazil before returning to Italy?

My great-great-grandmother did not intend to establish roots in South America as many migrant laborers from Italy did.

Career in trucking

She eventually did return to her homeland, only to found a country still struggling to find its footing as a new nation in its 30th year.

The anticipated prosperity many Italians yearned for had not been realized in the late 1890s and early 1900s.

But in this new world, my great-great-grandmother found her future success.

She must have understood the financial struggles of the farmers in northern Italy, having been born into this agrarian life herself.

Also, she must have realized the potential profits for the farmers in the larger nearby cities, such as Venice.

The logistical challenge of bringing their harvest to big city markets was the problem my great-great-grandmother tackled when she obtained a cart.

She traveled to the various markets to tally the items they needed and brought this list to the farmers with whom she worked.

In turn, the farmers provided the necessary items that she transported to the markets in her cart. She and the farmers shared in the profits.

Her trucking operation, so to speak, was profitable enough to support herself and her family.

Work in silk production

Her entrepreneurial spirit and determination must have inspired and motivated her children, particularly her daughters.

A strong industry in Italy at the time was sericulture, the cultivation of silkworms for the production of silk, whose origins in the country date to the 12th century. (Allen, 7-8)

It was prevalent throughout the country, but eventually sericulture and silk manufacturing became concentrated in the northern region beginning in the late 1800s. (Allen, 51)

People interested in profiting from sericulture could raise silkworms from eggs to cocoons; grow mulberry trees to provide the worm’s main food source, its leaves; or both. The silk itself is essentially a filament created by the worm in the cocoon. Mulberry trees with their large canopies and thick, gnarled trunks thrived in the fertile soil of northern Italy.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, more than 1.5 million Italians worked in the sericulture industry.

The average annual yield of raw silk from silkworms cultivated in Italy was about 10 million pounds with a value of between $45 million and $50 million. (Allen, 51)

Today, that industry would be worth more than $1.3 billion after factoring in inflation.

One of my great-great-grandmother’s daughters was among the thousands of northern Italians who made a livelihood from this industry by raising silkworms.

It is not known whether she and other family members cultivated them through a cottage industry or she worked for a local factory.

More than 40 manufacturers using power looms were operating in northern Italy at that time. (Allen, 51) Her daughter likely supplied silk to one or more of them for the creation of silk stockings.

Serving noble families

Two other daughters turned to the houses of local nobility for their employment.

Several noble families lived in northern Italy from the beginning of the country’s unification to 1915. Some of these families may have inherited these titles as is tradition, but many might have actually applied for their ranks and received a patent of nobility.

The grueling bureaucratic process for ambitious aspirants required them to provide proof of their wealth, charitable works, public service and influential supporters. In the nearly two decades before World War I, a third of these nobility patents were issued to businessmen and bankers. (Cardoza, 599-601)

My great-great-grandmother’s two daughters worked in the home of a count. One labored in the kitchen while the other served as a nursemaid. The latter tended to and entertained the children and often attended the opera with them as well as participated in other outings. This daughter became my great-grandmother.

I did not fully appreciate my great-great-grandmother’s life until I became a single parent. Her desperation, courage and ingenuity leave me simply spellbound.

This is her story, but she is not alone. So many single parents have endured and overcome great hardships. And to all of you, I say thank you for not giving up!

Allen, Franklin. 1904. The Silk Industry of the World at the Opening of the Twentieth Century. The Silk Association of America.

Cardoza, Anthony L. 1988. “The Enduring Power of Aristocracy: Ennoblement in Liberal Italy (1861-1914).” Publications de l’École Française de Rome. Vol. 107. pp. 595-605

On Thursdays, I will be sharing a blog about a day in the actual life of a single parent. Every fourth Thursday, instead of a personal post, I will put together one where I assemble news on and about single parents nationally and globally.

I would love to hear from you! Feel free to send any comments and questions to me at singleparentandstrong@gmail.com. I am also on Twitter @parentsonurown and can be found by searching #singleparentandstrong.